Born in the USA: A Look at the US Exchange Landscape

The past 100 years have undeniably been an American century. The United States emerged from WWI an industrial, military and economic player, and from WWII the world superpower. Following the Bretton Woods Agreement of July, 1944, the US dollar became the reserve currency of a new global monetary order that would last until 1971. Even today, the US dollar finds itself on one side of about 88% of all currency trades.

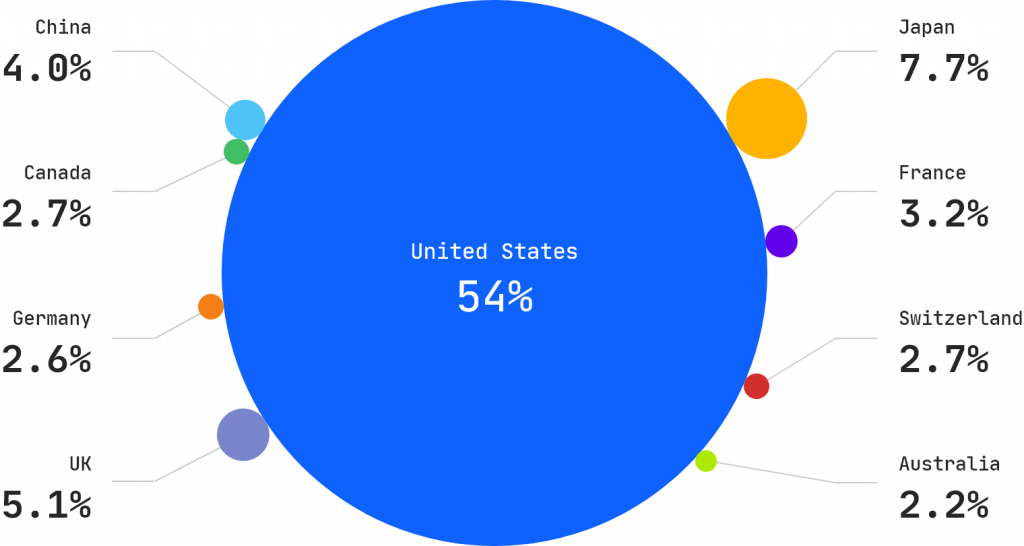

And it’s not just about FX. As of January, 2020, the US boasts the largest combined stock market in the world by far, accounting for 54% of the global market cap. To put things into context, the second largest belongs to Japan, at 7.7%. You see, Americans are known for doing things big, and this is why the US exchange landscape is, in many ways, a world unto itself. In the following article we’ll delve into this most exciting of markets, and take a closer look at the history and evolution of its four key players, Intercontinental Exchange, Nasdaq, Inc., CME Group, and Cboe Global Markets.

Humble Beginnings

Stock markets date all the way back to the 1600s in Western Europe where the Dutch East India Company became the first firm to issue stocks and bonds on the Amsterdam Exchange. This was also where other financial innovations such as derivative contracts and the practice of short-selling were pioneered. During the period, stock markets sprang up in places like Frankfurt, Copenhagen, London, Paris and Lisbon. They were used to further mercantilist economic policies by raising capital for exploratory voyages, international trade, and empire building.

In contrast, New York in the 1600’s was little more than a colonial backwater. Wall Street itself was just a short stretch of town where pilgrims built a wall in order to keep natives out. By 1792 the first organised securities trading in the city would come into effect as a result of the Buttonwood Agreement. The ragtag assortment of brokers, who reputedly signed the agreement under a buttonwood tree, would go on to form the New York Stock and Exchange Board, and eventually move from the Tontine Coffee House they were renting, to 11 Wall Street.

influential financial centers

The Birth of the NYSE

Today, the iconic building that stands at that address, and the newer venue at 18 Broad Street, are home to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the largest of its kind in the world with a market cap in excess of $30 trillion. Stock markets may have been born in the Old World, but they were destined to reach their zenith in the New World. Along the way, US exchanges have incorporated the advances of each era, leading to the development, expansion and interconnectivity of global markets. Some notable innovations, to name but a few, were the telegraph, the ticker tape, the stock index, the financial press, and the computer.

Today we’re accustomed to the practice of mergers and acquisitions, but the earliest versions of US markets were characterised by competing regional exchanges, all vying for the public’s trades. The invention of the telegraph made up-to-date price information available across the United States and was responsible for centralising financial power in New York. The name of the game then, as it is now, was liquidity, and the NYSE’s swelling books ensured that buyers and sellers could be matched quickly and cheaply.

In 1865, the New York Stock Exchange acquired the New York Gold Exchange. In 1869, the Open Board of Stock Brokers, a rival exchange also based in New York, merged with the NYSE, increasing its membership, liquidity, and bringing with it a superior continuous trading system to the NYSE’s twice-daily auctions.

More recently, in 2005 the Pacific Stock Exchange, originally based in San Francisco, California, was acquired by Archipelago Holdings. Archipelago Holdings merged with the NYSE at the end of 2005 to trade under the name NYSE Group. As of 2006, the Pacific Stock Exchange’s stock and option trades are conducted exclusively through the NYSE Arca platform.

The following year, the NYSE Group would complete its merger with Euronext N.V, the largest stock exchange in Europe, operating markets all across the European Union. The merger gave birth to NYSE Euronext, the first transatlantic exchange. In 2008, NYSE Euronext acquired the American Stock Exchange (AMEX), eventually rebranding it as NYSE American, where small and micro cap US company stocks are traded.

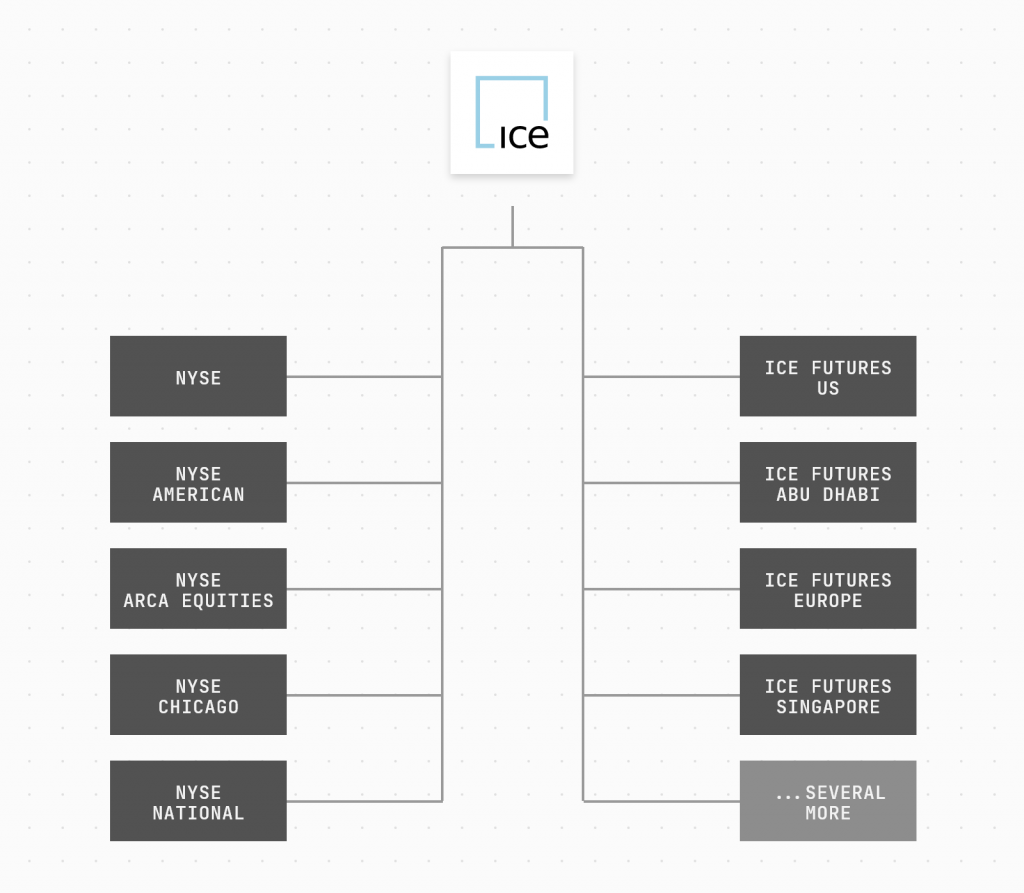

In 2013, after a proposed merger between NYSE Euronext and Deutsche Börse was blocked by the EU, Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), a Fortune 500 financial services firm, acquired NYSE Euronext. It kept NYSE and the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange (LIFFE), while spinning off Euronext. Today, ICE is the third largest exchange group in the world, operating equities, bonds, futures, options and over-the-counter (OTC) markets in the US, Europe, Singapore and the Middle-East.

Other notable acquisitions include Standard & Poor’s Securities Evaluations (SPSE) in 2016, the Chicago Stock Exchange (CHX) in 2018, and Ellie Mae Inc., a technology company that processes 35% of all US mortgage applications, in 2020. At $11 billion, this last acquisition is the largest in the company’s 20-year history.

In September 2019, ICE launched Bakkt, an exchange offering the first ever regulated, daily and monthly physically deliverable bitcoin futures contracts. The move has been regarded as one of the first steps in legitimising the cryptocurrency space and attracting institutional investors to it.

Nasdaq, The Stock Market for the Next Hundred Years

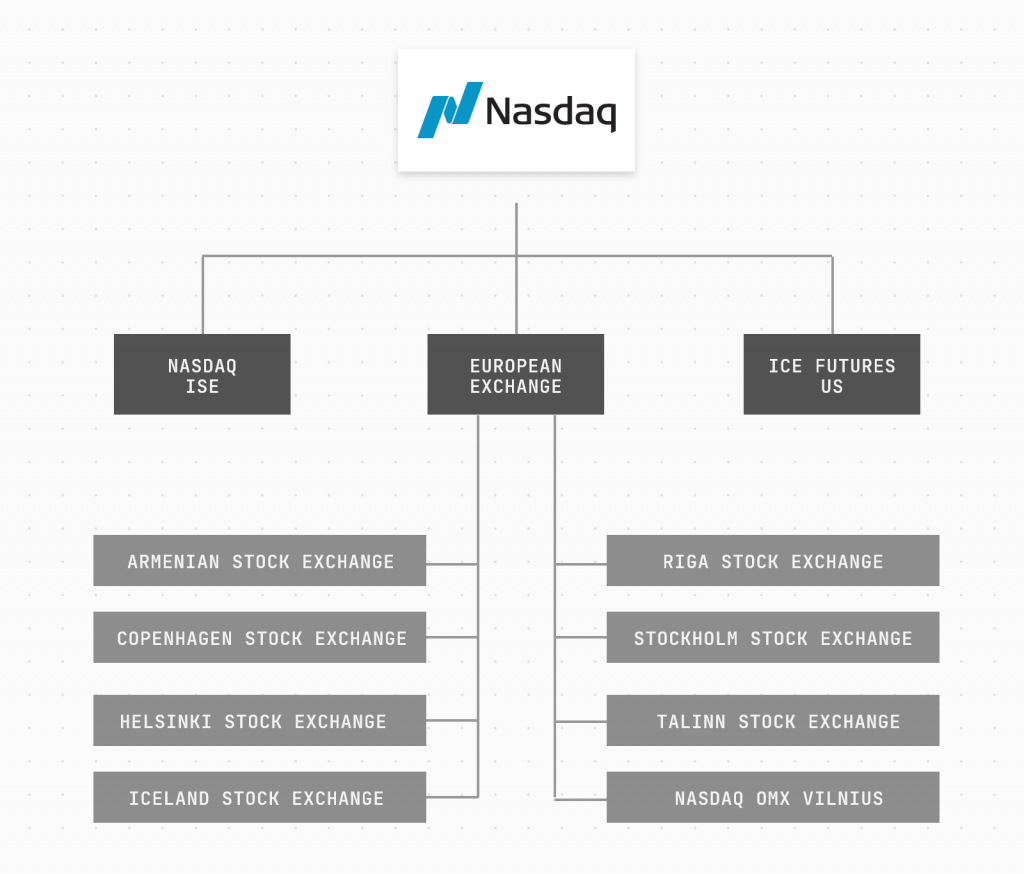

The Nasdaq is the NYSE’s younger, more technologically savvy, sibling. Originally an acronym for the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations, the New York-based Nasdaq is the second largest exchange in the world by market cap and boasts several firsts in the history of exchange trading. Upon its launch in 1971, it became the world’s first electronic stock market. A partnership in 1992 with the London Stock Exchange created the first intercontinental link between markets. In 1998 it became the first US stock market to trade online, billing itself as “the stock market for the next hundred years.” Finally, in 2016, when the company’s COO, Adena Friedman, was appointed CEO, she became the first woman to head a major US exchange.

billboards in the heart of Times Square in New York City, USA. The billboards continuously

display commercials, news, and information on upcoming IPOs

Speaking in 1998, on the eve of the dot-com bubble, its then president, Alfred Berkeley, made some highly prescient statements on the future role the Internet would play in markets. “I believe the Internet is one of the transforming technologies in our lifetime…. I believe that it changes everything that I have to deal with in the market because it changes the cost equation… This is either going to be my friend, or it’s going to be my enemy, and we’ve decided at Nasdaq to aggressively embrace these new technologies.”

The Nasdaq’s parent company, Nasdaq, Inc., was also a key player in the proliferation of market data. The digital nature of its exchange allowed the company to capture, store and resell market data at unprecedented levels of granularity. In that same 1998 address, Berkeley also outlined Nasdaq’s aspirations as a data vendor, explaining the different levels of aggregation required by different potential customers, from academia, to the corporate world, and on to individual investors.

“We’re taking all the trading information that comes out of our market and putting it into a very large, real-time database. It’s a huge amount of information because we’re capturing every tick, every error corrected, every quote change, every trade, and we’re making that information available to all those different constituencies at the level of aggregation they’re interested in.”

It was this approach that allowed new players such as the Nasdaq to gain market share from incumbents such as the NYSE, especially with the rise of high frequency trading, forcing them to evolve or be left behind. The trend towards digitisation of markets is also partly responsible for the massive consolidation that’s taken place in recent decades, with international mergers and acquisitions having become the norm.

For the reasons outlined above, Nasdaq’s own mergers and acquisitions are relatively thin on the ground compared to the NYSE. In 2007, Nasdaq, Inc. acquired the Boston Stock Exchange, and in 2008 it acquired the Philadelphia Stock Exchange. In the same year it also completed its acquisition of OMX, a Swedish-Finnish firm that runs several Nordic and Baltic exchanges, to form Nasdaq OMX Group. In 2012, the group also acquired the multimedia, investment and public relations businesses of Thomson Reuters.

CME Group, The Biggest Financial Exchange You’ve Never Heard Of

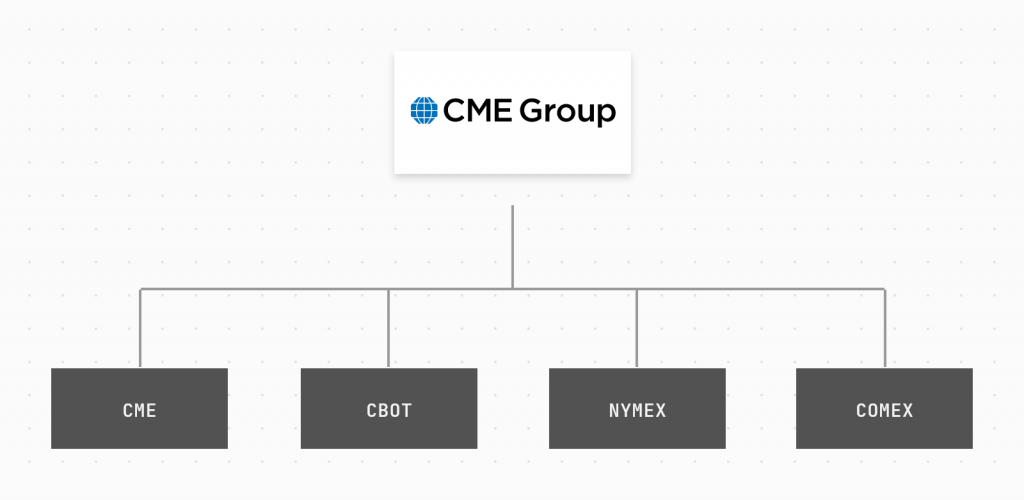

CME Group Inc., the umbrella entity that owns and operates the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), the New York Mercantile Exchange, and the Commodity Exchange (COMEX) is the world’s largest derivatives exchange. Whereas the NYSE and NASDAQ started out as stock exchanges that have subsequently expanded their available asset classes through various mergers and acquisitions, CME Group focuses exclusively on the trading of derivatives. Derivatives are contracts that derive their value from underlying financial assets or instruments, and as such, can be traded without the possession or delivery of said assets.

US city

Founded in 1848, the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) is one of the world’s oldest futures and options exchanges. Forward contracts had long been used to allow producers to secure a price for a commodity to be delivered at a future date. This essentially allows each party to eliminate uncertainty by fixing a price in the present. In order to minimise credit risk, the CBOT was formed so that buyers and sellers could trade with each other in a centralised location under a given set of rules. In so doing, the CBOT pioneered the world’s first futures contracts for grain, as well as the first ever clearing operation by requiring participants to post margin.

Futures function much like forwards, except they are traded over an exchange and are standardised in a manner that makes futures contracts for a given commodity interchangeable. Over the next 130 years, the CBOT would introduce a number of other futures contracts including soybeans, chickens, silver and interest rates. In 2005, the CBOT went public, listing its shares on the New York Stock Exchange.

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), originally called the Chicago Butter and Egg Board, was founded in 1898 to facilitate the trading of those two agricultural commodities. In its earliest days, futures contracts were only a small part of its operations. In 1919 it was renamed the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the following decades would see it expanding its operations to include other kinds of futures contracts such as frozen pork bellies, live cattle, currencies and stock indices. In 1987, it began developing the first ever electronic futures trading platform, CME Globex, which launched in 1992 and revolutionised the trading of futures contracts. In 2002, it became the first US exchange to go public, listing its shares on the New York Stock Exchange.

The CBOT and the CME merged in 2007 to form CME Group, the world’s largest and most diverse marketplace for futures contracts. In 2008, CME Group acquired the New York Mercantile exchange (NYMEX), adding energy, metals and more agricultural commodities to its contract offering. In the same year, the group initiated a partnership with BM&FBOVESPA, South America’s largest derivatives exchange, that would allow BM&FBOVESPA products to be traded on the CME Globex platform. In 2012, CME Group acquired the Kansas City Board of Trade (KCBOT), adding hard red winter wheat contracts to the existing soft red winter wheat contracts it gained after merging with the CBOT. In December 2017, CME Group launched bitcoin cash-settled futures, with each contract representing five bitcoins.

Back in 2013, The Economist ran a piece on CME Group with the subheading “the biggest financial exchange you have never heard of,” praising the group’s strategic mergers and acquisitions that focused on broadening its product offering rather than building relationships. It also lauded the Group’s switch to electronic trading, and the timeliness of its currency futures tied to the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), just as the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates was falling apart after the Nixon Shock of 1971. Today, 90% of its volumes are generated on its CME Globex platform, and its currency and stock index futures account for the lion’s share of its business.

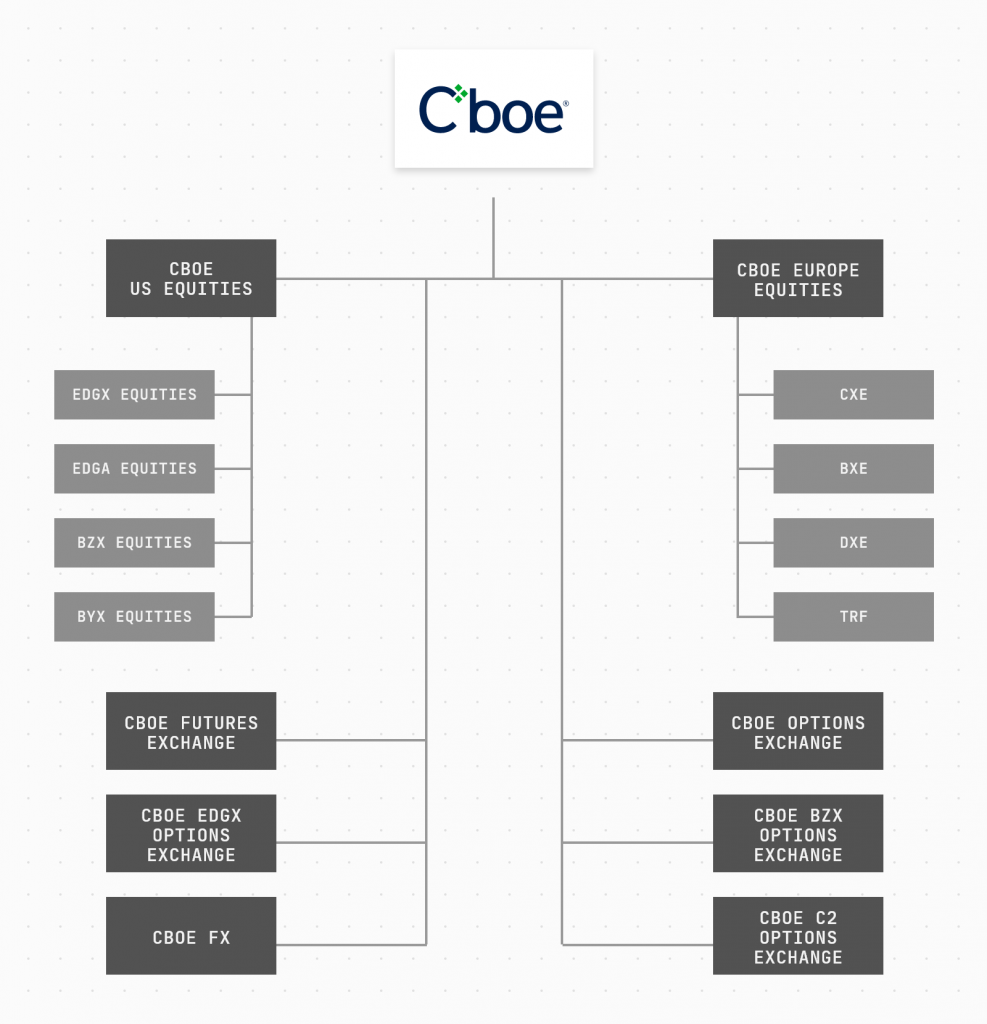

Cboe Global Markets, Options to Buy and Sell

Another relative newcomer, the Chicago Board Options Exchange (Cboe) was founded in 1973 by the CBOT and became the first marketplace for trading standardized options contracts. It is currently the largest options exchange in the United States, and has been central to the development of the options market. Its parent company, Cboe Global Markets, offers trading in US and European equities, European derivatives, FX and futures.

(CME). CBOT founded the Chicago Board of Options Exchange (Cboe)

In 1977, the Cboe expanded its options offering by acquiring the Midwest Stock Exchange’s options business. In the same year it introduced “Put” options, allowing sellers the ability to sell an underlying asset at a specified strike price in the same way as “Call” options allow buyers to buy given assets at set prices.

In the 1980s, it introduced a number of new options contracts, such as stock index options on the S&P 100 and S&P 500 in 1983, and interest rate options in 1989. In 1990, the Cboe introduced Long-term Equity Anticipation Securities (LEAPS), allowing investors to trade equity options with 3-year expirations. The rest of the decade would see the introduction of options on specific sectors of the economy, international indices, the Nasdaq 100, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Perhaps most notably, in 1993 it launched its own index, the Cboe Volatility Index (VIX), which to this day remains the preferred measure of market volatility.

In the early 2000s, it launched its own electronic trading platform, Cboedirect, introduced short-term weekly options, and opened its own futures exchange where it began offering contracts on its VIX volatility index. In 2010 the company went public, creating Cboe Global Markets and listing its stock on the NASDAQ. Following the IPO, it began expanding into equities with the acquisition of National Stock Exchange in 2011, and BATS Global Markets in 2017. At the time, BATS was the third largest equities exchange in the United States. In the same year, the Cboe Futures Exchange became the first regulated exchange to offer cash-settled bitcoin futures, one week before CME Group launched their own bitcoin offering . Today, the portfolio of Cboe Global Markets includes four options exchanges, seven equities exchanges, one futures exchange and one marketplace for FX.

Almost as American as Apple Pie

The United States is unique among other nations in just how interlaced its markets are with the daily lives of its populace, particularly its stock markets. Whether it be the passive flows into equities from mutual funds and exchange traded funds that people’s 401(k) contributions are allocated to, or the volumes generated by individual investors trading their own books.

A recent Gallup poll revealed that in 2020, 55% of Americans hold stocks. This figure is down slightly from the highs of 62% on the eve of the Great Financial Crisis. While the citizens of other nations pay little mind to the changing fortunes of the companies composing their national stock markets, in the US the stock market is king, and is considered a proxy for the health of the entire economy.

In 1998, Nasdaq president Alfred Berkeley predicted that shifting demographics would lead to a situation where there were not enough workers to take care of the retirement needs of an ageing population. He saw governments moving from “we pay you” pension programmes, to a “you need to save for yourself” model, and expected a sizeable chunk of those savings to find their way into equities. In the US, at least, that seems to be precisely the way things have played out.

Such is the relationship of the American people with US stock markets, they participate in their excesses and suffer their collapses like no other. From the Great Depression, to the Dot-Com bubble, to the GFC, each crisis was preceded by a speculative mania in which a few made fortunes and many lost everything.

The Future?

If there is a trend to be observed, it’s that technology is making markets more accessible and democratic, while also spreading financial literacy. A generation ago, your average person couldn’t tell an order book from an onion, today people build investment portfolios at the bar from their smartphones. Perhaps it’s trite to say that trading is eating the world, but it certainly looks that way.

In the past decade, the explosion of cryptoassets, a largely retail-led phenomenon, has caused the traditional financial system to sit up and take notice. All manner of players, from central banks, to governments, to corporations are currently in some stage of experimenting with their own digital assets. Last year, Facebook announced plans to create its own digital currency and payments network called Libra. Recently, the Chinese government began piloting a digital version of the yuan. Just the other week, the IMF’s Managing Director, Kristalina Georgieva, gave a speech calling for “a new Bretton Woods moment,” before hosting a virtual panel on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) and Global Stable Coins (GSCs). Digital currencies are a prelude to all other assets being digitised, because you can’t have a scenario in which money can be sent anywhere instantly, but a stock trade takes two working days to settle.

Perhaps, just like the computer revolutionised trading, cryptography will soon revolutionise the very assets being traded. This could lead to a situation where everything can be tokenised and everything traded. Where you can invest in the people, firms and causes you care most about simply by holding their tokens. Where dividends are airdropped and trading is entirely frictionless. One thing is certain, the humble tried and tested exchange, where buyers and sellers have been meeting in the middle for more than 400 years, where the bulls and bears are engaged in a perennial battle for supremacy, is definitely here to stay.

This article is the second installment of our series on the democratisation of market data and introduction to Market Data Vendors. If you missed the first article, you can read it here Behind the Charts: a Brief Introduction to Market Data Vendors.